An effective health policy is based on the principle that health is a fundamental human right. In our visits to Burkina Faso, talking to health workers, we realised that Burkina Faso fails to respect this principle for two reasons: scarce economic resources and scarce human resources.

Health care is paid for despite the fact that the population is financially unable to afford it. Very often, the few people who manage to start treatment are forced to discontinue it for lack of money, thus thwarting professional and economic efforts and often creating new problems, such as bacterial resistance to antibiotics.

The difficulties then increase disproportionately when one moves from the big cities to remote villages in the savannah from which it is very difficult to reach the few hospitals located in the cities.

I was struck by the scene of so many mothers queuing in front of a hospital of a humanitarian organisation to have their sick children examined. The queue is always interminable, under the scorching sun or in the rain; as a ‘placeholder’, the mothers use the health booklet placed neatly on the ground with the others, but often also a piece of plastic, a piece of paper tied to a rock, … To see all these improbable placeholders on the ground, they look like one long ‘snake’ of suffering.

In recent years, there has been a considerable increase in health infrastructures in the territory, but it must be pointed out that the situation is still characterised by a different geographical distribution between urban and rural areas.

This does not allow all Burkinabè to have access to a health centre or other forms of assistance.

The health system in Burkina is financed by

– state budget

– external aid (NGOs, and various)

– population and households

Through the external aid of NGOs and international bodies, hospitals are built and the population is offered assistance, but these efforts of international cooperation associations, however laudable they may be, are largely insufficient in relation to the needs of the country.

In the end, it is the citizens themselves who contribute most to the financing of health care, especially by charging for the costs of services and medicines.

Due to the generalised poverty, the population unfortunately very often finds itself financially unable to meet the costs of even a mildly serious illness.

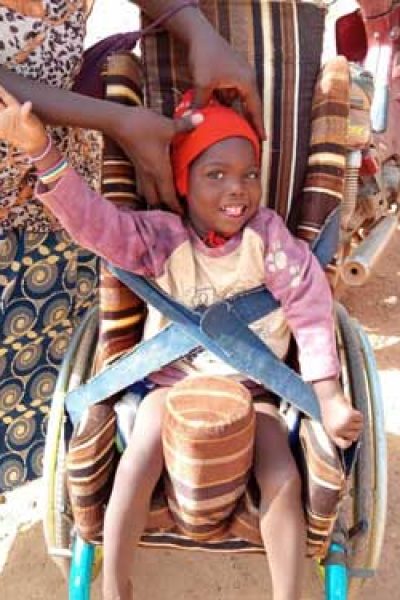

During the November 2010 mission, the presence of two friends and doctors, Mauro and Monica, allowed us to try to bring medical assistance to two places where we knew we would have to stop for other activities: the Akova family home in the capital and the seminary in Kaya.

This activity was an experiment without any pretense of solving Burkina Faso’s health problems or substituting ourselves for various medical structures operating in the country.

We just wanted to bring help to the many patients suffering from minor ailments that are completely forgotten in this country. This causes insignificant pathologies to turn into serious problems that affect people’s lives.

I am not a doctor, so you will allow me some inaccuracies, but I mean that an untreated ear infection degenerates into a burst eardrum, just as a simple untreated cough can degenerate into pneumonia, a sight defect in a child that can be cured with corrective glasses costing a few euros degenerates into sight anomalies that can no longer be resolved, …

So we brought with us all the medicines we had been given in Italy and which we could fit into our capacious suitcases, then we talked to the contacts at Akova and the Kaya seminar, who drew up a list of sick people and gave an initial assessment of severity. On the basis of these lists, Mauro and Monica visited dozens and dozens of people non-stop, giving almost all of them remedies and medicines. When the pathology was serious or impossible to diagnose with the few means available, we sent the sick to the nearest hospitals for specialist visits or specific analyses at our own expense. We often paid for glasses, which fortunately in Burkina Faso are made, among others, at the San Camillo hospital, which applies ‘social’ rates.